Herbst 1967 - The Fisher Handbook - Teil 2 - ab Kapitel 9

Auch "The Fisher" hat es gemerkt, die modernen Hifi-Stereo Produkte sind erklärungsbedürftig und der Markt ist noch lange nicht reif, von allein zu kaufen. Die Interessenten, die überhaupt auf diesen Zug aufgesprungen waren oder gerade am Erkunden waren, brauchten Hilfe.

Diese schwarz-weiß Broschüre im amerikanischen B4 Format hat schon richtiges Geld gekostet, doch der gesamte amerikanische Markt stand offen und das waren nicht unerhebliche Möglichkeiten. Fisher hatte sich den bisherigen Hifi-Markt mit nur ganz wenigen Mitbewerbern geteilt, die dort im oberen Bereich überhaupt etwas Vernünftiges anbieten konnten.

.

(9) Herbst 1967 - The Stereo Mods (steht für Kombinations- geräte) By Norman Eisenberg

Whether you think of "mod" as modern, modular, or even modest, the term aptly defines stereo's newest product form, also known as the three-piece music system. In these installations one cabinet (usually in walnut) houses a record changer and a control amplifier (sometimes with a tuner, making it a stereo receiver) and is known as the electronics module or, less austerely, as the control unit; two matching cabinets house a pair of stereo speakers. Such systems have also been called "compacts" - a term suggesting a place in the audio world somewhat akin to that enjoyed by compacts in the auto world: not as luxurious or as high-powered or as "last-word" as full-size, but fun to own, economical, and right handy for parking in tight spots. And most important, very competent performers.

While no one expects that mods will displace the all-out superiority of the best separates, everyone agrees that the new systems have permitted thousands of new listeners to enjoy well-reproduced sound. Which is, of course, the rationale behind the mods.

.

The engineering principle behind the stereo mods is component integration: record changer, cartridge, amplifier (or receiver), and speakers are chosen for their ability to work efficiently with each other at a predetermined level of performance commensurate with the system's cost. There is, in other words, a ceiling on the ultimate sonic splendor you can expect of a mod. It is a very high ceiling, but a ceiling nonetheless. And this really is what distinguishes the mod from a system made up of separates.

Directly responsible for this development is the use of transistors. Transistors are, in fact, the star performers here. They have made possible the design of audio equipment small enough, and cool-running enough, to permit its being closely installed in a common enclosure where record player and a full array of electronics share less than two cubic feet of space.

Also playing a major part in the successful design of the modular system is the improved response now possible with small speakers. Although the audio world still pays homage to the big systems or the costliest bookshelf types, there is a new peerage of compact and inexpensive performers.

The best of them are fairly clean-sounding, and audible differences are subtle. As a class, their bass output, while not overwhelming, is nonetheless convincing: they may not be able to re-create the lowest

pedal notes with the nth degree of exactitude, but they will permit you to recognize that it is an organ you're listening to and not a muddled version of an orchestral choir. The bass they provide is the result of their use of heavy magnets, driving small but efficient cones. This design technique has made for clean reproducers that literally can fit on a shelf and that do not require more than the ten to fifteen watts of amplifier power supplied by the electronic module in order to provide clean bass down to about 60 Hz.

The mid-range and highs in these systems generally are handled by an additional speaker designed for fairly wide-angle dispersion and clean tones up to or just beyond about 14 kHz. While all the elusive highs and the sense of ultimate air and space that you might hear from a costlier, more elaborate speaker system may be missing, you will get the best part of the important overtone structure of music - which will certainly let you distinguish easily between, say, the strings and woodwinds in the upper register. Most important, these systems have a well-balanced output and do not favor one portion of the musical spectrum over any other: they will neither shriek at you nor blast your ears with overheavy thumping bass. And most of them are quite good at handling transients, those short-duration sonic pulses that lend a touch of realism to reproduced music. Over-all, these systems can fill a normal size room with very listenable sound.

Transistors, small speakers-and style. The stereo mods have an immediate easy-to-live-with quality, a quality built-in and ready-made and apparent as soon as you start unpacking the cartons. Aside from their obvious visual appeal, there is the tidy thoughtfulness with which everything is arranged and planned; the prefitted cable connectors neatly bundled and ready to be plugged in; the cartridge already fitted correctly in the arm shell; the freedom from guesswork in determining what size or length of wires to use for hookups; the little fillips in some mods, such as the option to select a colored grille cloth, or the inclusion of a stylus brush on the record changer or a unique just-right arrangement of controls and indicators. You get a feeling that someone finally has taken the trouble to make everything as easy as can be for stereo enjoyment but without, as a concomitant, seriously limiting or compromising the performance.

Condensed from High Fidelity. Copyright by the Billboard Publishing Company.

.

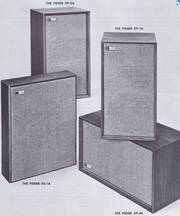

(10) Speakers: Large, Small and In Between (groß oder klein ?)

By Bob Marx

One of the fruitful and pleasant things about shopping for the speakers with which you intend to cap a stereo sound system is that there are differences to be seen and heard among the many models typically found in an audio showroom. Differences of appearance among today's speaker systems are very obvious, while the differences in sound are more subtle but perceptible nonetheless. It is something of a challenge, of course, to eliminate the speakers with evident deficiencies from your shopping list, and then go on to pinpoint and evaluate the audible differences between good speakers. But it is an enjoyable kind of challenge, and one that can heighten your involvement with stereo.

It is worth making clear that the number of individual speakers or "drivers" employed in a particular loudspeaker system is not always a reliable guide to quality. While it is true that many designers of perfectionist speaker, systems use three, four, or even more speakers in a single system, it is equally true that the makers of mass-market radio-phonographs often use cheap speakers in multiples to mask mediocre quality and woo the unwary buyer with the appeal of sheer numbers.

The argument for the small speaker is that it can be mounted in a relatively small cabinet easily accommodated in a living room, and that the air trapped in the small cabinet can exert a very uniform control over the motion of the cone (by "air suspension"). For the proponents of the larger speaker systems the chief argument is that the speaker moving a shorter distance for bass reproduction does so with audible ease and with greater efficiency-that is to say, it requires less power from the amplifier.

There is no doubt at this time that very good speaker systems can be found in both small and large sizes. The question of size as such is hardly one of great differences in sound, but rather of other factors such as personal taste, and of amplifier power, and the amount of space available in a living room.

The new emphasis from many manufacturers on the importance of high frequencies for "big" sound has had a very interesting (and highly welcome) effect on the speaker market over the past two or three years.

It is now possible to buy speaker systems in the "budget" category ($50 to $100) whose excellent high-frequency response provides decidedly spacious and well-defined sound quality. In the past, this price category implied definite and very audible compromises. Usually, in fact, the serious listener on a budget was best advised to choose an unpretentious speaker that could later become the mid-range unit in a more ambitious system.

But as things now stand, many will be able to find systems in the under-$100 range with which they will be able to live happily ever after. Just what can you get for your money in various price categories? To begin with, the category just mentioned contains many speakers offering surprisingly satisfactory sound. In addition to good high-frequency response, many of today's budget-priced systems offer a good semblance of the very-low-frequency reproduction - say, with listenable bass response to about 50 Hz or below - once available only for upwards of $200. Of course, the smallest systems as a rule are limited in power-handling ability, and would have difficulty in filling a 30-foot living room with sound at loud listening levels. But a few can stand up to this challenge-and all of the better budget-priced systems do provide balanced, eminently listenable sound at normal listening levels in an average size room.

In the $100 to $200 price range there are several speaker systems that are capable for providing just about everything in response that the serious music listener might value. In addition to extended highs and lows, and enough power-handling for the largest living rooms, systems in this range can, and often do, offer an over-all balance and freedom from distortion that makes for completely satisfactory long-term listening. For many listeners then, the $100 to $200 range begins to approach the point of diminishing returns.

There are, however, a significant number of models priced well above $200, and these offer continuing improvement of reproduction, albeit more subtly. That is to say, the amount of audible return per dollar becomes a matter of fine shadings in tastes and expectations. The differences between this and the last-mentioned price range are to be found in slightly more extended response at very low and high frequencies, in slightly less distortion over-all, and possibly in a greater sense of "air" and "spatial freedom" in the sound.

In the low-frequency range, by the way, the extension of response may be audible only with some of today's best recordings, and unless the rest of the system is near-perfect, a speaker with prodigious bass response may reveal turntable rumble or tone arm resonance or amplifier "breathing".

In the very-high-frequency area, extended response may make more evident such things as tape hiss, or the distortion and noise content of some records, or the high-frequency peak of a cartridge. Perfectionism in speaker selection, then, logically involves a concern over perfection in every other link of the music system, from the recordings played to the very room in which the speakers are installed. Settling for a lower-priced, but nonetheless clean, speaker system can thus afford a kind of "comfortable" listening that may not be of the perfectionist caliber but which still can be thoroughly enjoyable.

Condensed from Stereo '67. Copyright by the Billboard Publishing Company.

.

(11) How to Judge Speaker Quality with Listening Tests

(Herbst 1967 - Wie sollte man Lautsprecher beurteilen lernen ?)

By Larry Klein

How many times have you been advised in the pages of audio publications to listen for a speaker that has a "smooth uncolored sound?" Or a speaker that has a "non-peaky mid-range," a "non-boomy bass," a "good transient response," and so on? None of these terms, I'm afraid, adequately convey the particular subjective-objective phenomena that the author is seeking to describe. This has nothing to do with the much-abused subject of psychoacoustics, but simply relates to the very real question of how one can judge whether a speaker is doing a good job of reproduction when one does not have available for comparison the original sound the speaker is attempting to reproduce.

There is a popular (but fallacious) notion that it is enormously helpful, as a preliminary to speaker shopping, to attend a concert of live music. Unfortunately, the average mind's ear cannot be expected to isolate the distinguishing features of live sound under concert-hall conditions in the first place. And in the second place, the mind's ear is a notoriously leaky vessel and cannot retain the memory of what it has heard for more than a few seconds even under the best of circumstances.

Nonetheless, it is possible to make a valid judgment of the sound quality of a speaker in home or showroom once you become aware of what to listen for and how to listen for it.

An important aspect of a speaker system's bass performance is its freedom from spurious resonances. This can be tested simply by tuning in several FM stations and listening carefully to the various announcers on the speaker(s) under consideration. One or two of the announcers may have naturally deep voices, but if every one of them sounds as if he were addressing you from the bottom of an oil drum, you can be sure that the loudspeaker under test (not the announcer) has a bass resonance peaked somewhere in the 100-Hz region. This resonance provides for some a pleasant overlay of bass on classical material and enhances the beat on pop stuff, but the price paid for this is loss of upper-bass clarity and (usually) absence of genuine low bass.

As far as the high-frequency performance of the speaker system is concerned, a good test is to listen to recordings of music that includes cymbals or triangles and try to isolate the ringing or shimmering sound that is typical of these instruments. You'll find that some speakers will have the shimmer plus a liberal helping of hiss or surface noise, and that some will have the shimmer without the noise. Emphasized tape hiss or disc surface noise is usually the result of an irregularity in the speaker's high-frequency response, which may or may not audibly affect other aspects of its performance.

Another quality essential to good tweeter performance is wide dispersion - its ability to spread the high frequencies in a broad arc across your listening room. Without it, the sound will be closed in or boxy; with it, there is a sense of openness and airiness.

You can check for adequate high-frequency dispersion by using the interstation noise on an FM tuner (you may have to switch off the interstation-noise muting and AFC to do this). Tune between two stations to get the interstation noise (it has a rushing, hissy quality), and stand directly in front of the speaker. Then, concentrating on the hissy quality in the sound, walk off to one side of the speaker system; at some point you will find that the hissy quality disappears. You will find the same effect on the other side of the speaker - and probably, depending on where the speaker is installed, the hiss will also diminish if you duck your head toward the floor. The wider the area covered by the very high-frequency hiss, the better the high-frequency dispersion of your speaker system, and the more open and natural-sounding will be the music reproduced by it.

The overly bright and projected quality that comes from a boosted mid-range may be impressive on first listening, but it is accompanied by unfortunate side effects. Minor side effects are harshness (depending upon the range of the frequencies boosted) and emphasis of high-frequency noise and distortion in the program material.

The crux of the difficulty in evaluating speakers is knowing what to listen for. And that, in a nutshell, is the problem I hope this article has helped to solve.

Condensed from HiFilStereo Review. Copyright by Ziff-Davis Publishing Co.

.

(12) Room Acoustics: (5 allgemeine Probleme der Raumakustik)

Five Common Problems and How To Solve Them

By Peter Sutheim and Larry Klein

Well, you are finally ready. Having saved your pennies, done your audio homework, and researched the market to a fare-thee-well, you are about to buy the hi-fi system that is the best compromise between the conflicting demands of your heart's desire and your budget's limitations.

But have you neglected to consider the environment the music is going to be reproduced in? Trivial? Possibly, if your listening room has no obvious acoustic faults. But a great number of rooms do, and it is well to be aware of possible acoustical problems (and what can be done about them) before you start blaming your equipment.

.

- Problem 1: A common and obvious fault in some rooms, even to the untutored ear, is excessive "live-ness" - or, in the acoustician's language, excessive reverberation. The sound is shrill, hissy, or echoey, generally lacking in warmth, and stereo definition is almost completely lost.

- Problem 2: The converse of Problem 1, too much acoustical absorption (too little reverberation), seldom occurs with modern rooms and furnishings. But if your listening room is filled with thick rugs and drapes and heavily upholstered armchairs and sofas, the propagation and dispersion of high-frequency sound will be severely restricted.

- Problem 3: When the listener is seated in certain areas, he may hear a persistent bass "thrumming" that seems to fill the room and yet doesn't come directly from the speakers; in other areas of the room there may be no low bass at all. This is caused by a poor distribution of standing waves. When a room's dimensions are equal to half the length of a sound wave of a particular frequency, the reflections from the walls tend to establish a fixed pattern of pressure peaks and nulls at that frequency.

- Problem 4: Assuming (as we will do throughout this discussion) that your amplifier and speakers are not causing any of the faults you hear, one must look to certain properties of the listening room itself to explain the phenomenon of too little bass. This can be just as disturbing to pleasurable listening as too much bass or unequally distributed bass.

- Problem 5: The four defects mentioned above are private concerns. The fifth, transmission of sound beyond the listening room, may provide occasion for conversations with your neighbors-acrimonious or otherwise. Briefly, any sound produced in your listening room will be partly absorbed by walls, floors, and ceiling (and the coverings thereon), partly reflected and partly passed on to neighboring rooms or apartments.

.

Now that we have stated the various problems, what can we do about them?

If your listening room is too live (has too much high-frequency reverberation), it is possible that all you need do is reduce the high-frequency output of your system. This can be done either by turning down the amplifier's treble controls, or, better yet, by turning down the tweeter-level (and possibly even the mid-range) control on your speakers to reduce their high-frequency output.

If your problem is a little more extreme - if, for example, you hear speech sibilants bouncing back at you from a wall - you should make some changes in the acoustical character of the room. They can be as modest as rearranging the furniture, or as drastic as covering the walls and ceiling with absorptive material.

Low-frequency room resonance can usually be reduced by opening windows or doors into the listening room. An open door between two connecting rooms can profoundly alter the resonances of the combined spaces.

A small room - say, 8 x 10 x 12 feet - is unable to do full justice to the bass frequencies below about 100 Hz. This is not to say that a speaker system cannot deliver low frequencies into a small room, but simply that the room will not allow the speaker's full bass potential to be developed.

Note that small loudspeakers installed on or close to the floor will transmit less treble to your ears both because of the treble being soaked up by rugs (if present) and the bass reinforcement achieved by floor installations. Corner-mounting of speakers will also reinforce bass response. Mid-wall mounting will produce the least bass, and if your sound problem is either low-bass standing waves or simply too much bass, then a mid-wall shelf-mounting for your speakers may be the answer.

How about a large room that can't seem to propagate adequate bass from a pair of speakers that have bass to spare in a friend's house? Look to your speaker placement (the closer to the wall and the nearer to the room corners, the more bass) and to the wall construction.

It is rare that a solution cannot be found that will help to some extent. The ideal solution, of course, is to build-in good acoustics. And should you someday be in a position to design or buy a new house - or advise someone else - every trick you have tried, used, or rejected can be considered part of a useful rider on your audio insurance policy.

Condensed from HiFilStereo Review. Copyright Ziff-Davis Publishing Co.

.

(13) From Record Changers to "Automatic Turntables"

Ein Highlight im Prospekt sehr zum Ärger der Firma ELAC

Herbst 1967 - Der DUAL 1019 - By Julian Gorski

Long-established habits of thinking are never easy to change even when demonstrably obsolete. This is particularly true when it comes to the venerable debate of manual turntable vs. record changer. If we go back a few years, only one answer would have been accurate: the best performance could be obtained only with a manual turntable. For the convenience of automatic start and stop (single play or changer), some compromise in the quality of record reproduction had to be expected and accepted.

However, during the past three years, a new breed of record changer - the automatic turntable - has succeeded in closing this "quality gap."

.

Anmerkung:

"The Fisher" wurde etwa ab 1963 in Deutschland von der Firma ELAC in Kiel vertrieben. Vielleicht hatte man bei ELAC ja gehofft, daß "The Fisher" sich dafür in den USA - und vielleicht auch weltweit - für die ELAC PLatten-Laufwerke stark machen würde.

Doch dem war nicht so. Dual hatte es den Amerikanern angetan. Das Design des Dual 1009 war 1963 so außergewöhnlich progressiv und neu und anders als alles bislang Dagewesene, daß die Amerikaner in Scharen ihre eigenen Produkte einsammeln oder auch einstampfen konnten. Fisher hat seinen super tollen LINCON auch aufgegeben. Und jetzt erscheint in einem "The Fisher Handbook" ein Plattenlaufwerk des Wettbewerbers Dual. Und das sogar gleich zwei mal, nämlich bei dem Musterwohnungen auch.

.

Manuelle und automatische Spieler sind im Prinzip gleich gut !

For proof, we refer to the entire battery of tests - by both ear and instrument. Some of the tests used to measure and evaluate record playback equipment - for rumble, wow, flutter, tracking error, speed constancy, etc. - are basic to all types of record players, manual as well as automatic.

Other tests pertain only to the automatic - how thoroughly the tonearm is disengaged from the cycling mechanism when in play, how much force is needed to activate the automatic trip, how much tracking force is increased as records mount up on the platter during changer operation, etc. In both cases, the better automatics have earned comments like - "no gulf at all exists between manual and automatic."

Now, what has allowed an automatic turntable to earn such hard-won acceptance? Generally speaking, it has been vastly improved in design and precision manufacture that has not only kept up with the needs of the highly sensitive stereo cartridges but has actually surpassed them. For example, although most of today's cartridges call for a tracking force of about 2 grams, a well-balanced automatic tonearm can track properly as low as 1/2 gram.

This doesn't mean that you should try to track that lightly, but only that you should be assured that such a tonearm can do proper justice to whatever cartridge is used. (It's comparable to the comfort of an automobile with a top speed of 120 miles per hour being able to attain a cruising speed of 50 that much easier.)

Along with lightweight tracking - and 1 to 2 grams is quite light - comes the need for utter precision in both balancing the tonearm and in applying the desired tracking force. There's obviously less margin for error between 1 and 1 1/4 grams than there is between 2 and 3 grams or more.

Less obvious is the somewhat esoteric subject of skating, which has been receiving much attention of late. "Skating" is an undesired force acting upon the stylus that tends to move it toward the center of the record faster than it would be normally moved by the decreasing spiral of the record groove itself. This force results from the friction between the rotating record and the stylus in the tonearm head.

While not everyone agrees as to the magnitude of the skating problem, all do agree that it does introduce a measurable distortion that can be eliminated effectively by a properly designed anti-skating device. And while you might expect to find such precision adjustments only on the most costly of manual tonearms, you also will find them on the better automatic arms.

For many of the same reasons that call for such precision, convenience itself has also taken on new importance. Just try to handle a tonearm set for tracking at 1 gram and you'll appreciate the advantage of having it set down on the record for you ... and lift off at the end of play ... even though you may seldom play more than one record at a time.

Other features now offered by some include cueing devices for lowering and lifting the tonearm wherever you like on the record ... also without having to handle the tonearm itself. Even variable pitch controls are available for use by music students, tape recordists, or anyone else whose personal listening tastes might not be satisfied by a fixed factory-set speed.

Condensed from The Music Journal. Copyright, The Music Journal Inc.

.

(14) The Proper Storage and Handling of Records

By Charles A. Fisher

There are few things one can purchase that are capable of giving so much pleasure over a long period of time as a fine recording. It contains within its relatively delicate grooves the data that are brought to life as audible sound by your high fidelity system. As your collection grows it becomes the 'open sesame' to the vast and wonderful world of recorded music literature. Your records deserve, and will repay you for all the care you give them.

First, as to proper storage: All records should be stored vertically, never horizontally. Neat, vertical storage places all the weight on the record's edge, preventing warpage. In planning the storage shelves, it is best to have these of a depth of the average LP record cover (or approximately 12"). This will permit your records to overhang the front edge of the shelf, making it much easier to withdraw the desired record by grasping the top and bottom edges. (See Figure 1).

.

Multiple record albums may require greater depth and it is more practical to construct the shelves deep enough to accommodate the largest albums, measuring from front to back, and then inserting the proper size cleat at the bottom rear of those shelves used for single record albums (Figure 2) so that these will still overhang the front edge by the same amount as deeper albums. The less clearance above the top of the stored records, the less opportunity there will be for dust to settle in this area.

Dust and oil, which are ever present in the atmosphere and on normal skin, are the greatest enemies of record life. Conversely, clean recordings played with a good quality cartridge capable of proper operation at low stylus pressures will, for all practical purposes, last almost indefinitely.

Cleanliness, from the outset, is easy to acquire (for most records are sold in sealed plastic covers), and as easy to maintain. After opening a new record album, remove the record, holding it by the edges, not the recorded grooves. Hold the album cover open and blow vigorously into its interior. This will remove residual dust that may have found its way into even a new record cover. If this is done periodically, even records stored without plastic sleeves will be spared the scratches that come from dust trapped in the covers. Never leave a record on the turntable after it has been played, but blow on both surfaces to remove dust and store it immediately in its album.

Moderately dusty records can be restored to clean condition by an easy, no-cost method. Simply hold the record in your left hand under a stream of cold running water, meanwhile running the fingers of your right hand gently through the stream of water, across the face of the record, to loosen any dust that may be adhering to the surface. Avoid excessive wetting of the label. (This is easily accomplished by inclining the record toward the faucet and rotating the playing surface slowly under the faucet, with the label just beyond the reach of the water. (Figure 3). After washing, briskly shake off the excess water and remove the final drops by running a tissue lightly across the surface. (Figure 4).

Records that are heavily soiled can be restored to clean condition by careful washing in a basin of detergent water, followed by a clear-water rinse as described above. In both cases, one should avoid over-soaking the label.

We do not recommend the use of record cloths because dust inevitably trapped in these materials convert them, in a sense, to an abrasive. If rubbing is necessary to remove adhering dust, it should be done only in the presence of a good lubricant. (Running water is a splendid lubricant, when used under the technique described earlier.)

In summary, for the preservation of your record library, you will quickly find that there is no substitute for consistent and simple care, utilizing the methods noted.

(15) Herbst 1967 - How To Buy a Tape Recorder

By Paul Edwards

Is this your first time out in the tape recorder market? Or maybe your first recorder was a disappointment, and you are looking for a better buy. In either case, take a few quiet moments to consider what you want from what is available. To begin with, determine how you intend to use your recorder. Do you need high fidelity capability for musical recording and playback? Do you need special equipment and/or accessories? These are important to your choice of equipment-to ensure that you don't underbuy and aren't over-sold.

The next bit of preparation involves money. Decide from the start the limits of your price range. And make it a range, so that you have some flexibility in matching need with cost. Like a good poker-player, you won't be pushed into more than your wallet can bear. And on the other hand, it's quite possible to come out of the store with exactly the piece of equipment you need, at less money than you expected.

Your final step is to acquaint yourself, in general, with the equipment you intend to buy. Here are some of the more salient features of a tape recorder. Familiarize yourself with them, before you buy.

.

- 1. Motors. The two most widely used motors in tape units are the hysteresis synchronous, and the four or six-pole shaded. The hysteresis is the more expensive of the two, but often the more reliable. It is able to resist the effects of sudden changes in voltage, such as occur almost daily in urban power lines. The four or six-pole shaded motor is found in less-expensive machines and does not resist power changes.

Most medium-priced recorders use a single motor to drive the tape transport. More expensive models use two or three motors. This usually offers a smoother tape flow, and high-speed rewind and fast forward. - 2. Speeds. The standard for home use is still a speed of 7 1/2 inches per second (ips), (but 3 3/4 ips may soon be the standard). It provides a relatively long-recording-time with good fidelity. Many pre-recorded tapes are produced at this speed. The slow 1 7/8 ips speed offers maximum capacity per reel and quite adequate fidelity for speech, such as dictation. Today, most tape recorders offer more than one speed, for both recording and playback.

- 3. Heads. A good recorder has at least two heads - one for combination record and playback; the other for erase. This arrangement allows substantial flexibility. You are able to record new material, play back the material for listening, and erase it in order to make a new recording. Most professional recorders utilize three heads to do the job. It is obviously a more expensive arrangement. But it does allow you to monitor the material as you make the recording. It can alsc be used for adding special effects to a recording.

- 4. Automatic Reverse. This feature simply allows a tape to play back in both directions. This means that once a reel is unwound, the tape will automatically reverse itself and continue to play as it rewinds on the original reel. It will add to your cost. Only a few tape units allow recording in reverse as well as playback. There are also semi-automatic units, requiring a manual step to accomplish the reverse.

- 5. Automatic Threading. We live in a Convenience Society. So here is a convenience feature to combat the often annoying problem of threading the recorder. Automatic threading may take the form of reels that anchor the tape once the end is laid on it, or it may take the form of a self-contained cartridge.

.

Condensed from Tape Recordings 1967 Annual Buying Guide Copyright 1967 by A-TR Publications, Inc.

.